Recently my friend and colleague Elaine Vickers drew an important distinction between being a writer and being an author. At first the distinction seems obvious. A writer’s work is the plain craft of telling stories. We can learn it from our reading, from our evaluating our own work, from workshops, classes, revision, and from reading what other writers have had to say about the craft. Author’s work is something else entirely, and I’ve discovered (as many have) that it is a lot more difficult to learn.

I have a master’s degree and PhD in creative writing, and I have taught writing at the university level for a lot of years, and I don’t think you can teach writers to be authors. You might be able to save people a little time, but in the end being an author is something you learn directly from people who have gone down this road. It comes from mentors.

This post isn’t about how to get a mentor, though that is a straight-up important subject, and something to take up another time. In this post, I’d like to share some ideas about being a mentor.

As Sheryl Sandberg points out in her book Lean In, mentorship can’t really be requested (it always comes off wrong), but it can be offered. There are thousands of stories floating around about the bad behavior of well-meaning but desperate people who know they need mentorship but don’t understand that they won’t find a mentor by following them into the bathroom.

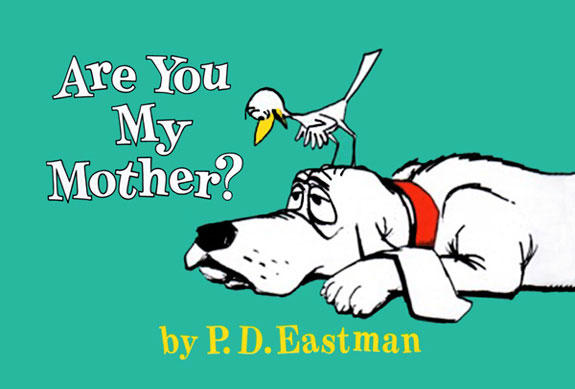

Sandberg talks about how people looking for mentors sound like the bird from this childhood classic, asking “Are you my mother?” This is pretty cringe-worthy for everyone. Sandberg spends a lot of time in the book discussing the ways leaders can make a difference by keeping their eyes peeled for proteges.

Sometimes mentoring comes through a sustained relationship, and sometimes it comes from serendipity, but the mentor should be the one to make the offer. A year or so after college, I was having brunch with my mother in the Heathman Hotel, and I kept looking at an older gentleman across the way. He and his wife were having breakfast with another man and his wife.

My mother said, “Hey, you’re being rude.”

I said, “I think the guy is William Stafford. He’s, like, my second favorite poet.”

“You should wait until they get the check and then go say something to him, but skip the part about him being your second favorite.”

I waited until the server dropped the check, and I walked over, “Excuse me,” I said. “Are you William Stafford?” I asked.

The man’s wife chuckled, and he said, “Yes, I am.”

I told him I really enjoyed his work, that I’d been exposed to his writing in a literature of the Pacific Northwest course I took while I was at the University of Oregon. He asked who taught the class. He asked who else was on the reading list, and I ran through it. I ended saying the professor included Ivan Doig’s This House of Sky in the course, even though he wasn’t sure Montana counted as the Northwest. Everyone at the table laughed, and Stafford said, “Well, you’re in luck today. That red-headed rascal across from me is Ivan Doig. Maybe he can clear things up.”

These two men asked me about my own writing. I didn’t have much to say, but I was honored that they’d ask. At the end of this short conversation, Stafford said, “If you don’t have plans, we’re going over to the Oregon Historical Society for symposium on Western writers. You’re welcome to come.”

I thanked them, shook their hands, and tried not to be too star struck, then I went back to our table and said, “Um, I know we have somewhere to be, but they just invited me to go to a writer’s thing. Can we go?”

That encounter was so simple and generous, and it changed me forever. I learned that writers were real people, and you could meet them in a hotel restaurant. It planted the most simple idea in my head that I could do this, too. What it has also done for me is give me a template for how to be gracious to those who are just starting. It showed me that everyone needs to be on the lookout for the new person coming down the road.

On the couple of occasions that I’ve done work with high school writers I’ve found myself in a similar situation, not as the new guy, but as the person who was a few steps ahead. At the end of a reading or workshop, there’s always one kid (sometimes more) who lingers. I love these people. They’re usually from small towns where the ratio of athletes to artists is something like 66:1. Their questions are all cut from the same cloth.

- Do you write everyday? (I try.)

- What software do you use? (Ulysses.) What’s that? (It’s complicated.)

- Where do you get your ideas? (It varies but mostly from sitting in diners.)

- How do you keep writing when you don’t want to write? (I signed a contract. I know this is the worst answer ever.)

I love these questions, and I hate them. There is a part of me that wants to sit these people down and say, “There are no short cuts.” I know they want this to go faster than it does. I spent decades wanting things to go faster than they do. I wanted getting an agent to go faster than it does. I wanted being out on submission to go faster than it does. I wanted the contract to come faster than it does. This isn’t good mentoring, though. And I have to remember that I was once that kid crossing a restaurant to introduce myself to a poet.

Advice is really important, and when it’s about the author’s work, it’s hard to come by. Right as I went out on submission, I got some amazing advice from one of the writers who wrote some advanced praise for my manuscript. He sent me an email with the subject line: “keep typing.” The message inside that email was just as important:

Hi Todd:

Good luck as everything creeps forward! The ticket is to work quietly on your new project whatever it is. We’re writers.

What spellbindingly good advice. I didn’t ask for it, but there it was just the same. At that point, I realized at some point in the future, I’d be in a position to send an email with the subject line: “keep typing,” and I will.

I don’t believe writers have an obligation to mentor, but we really do have to help each other along. Anyone who makes headway in this game needs to pay it forward. At least that’s how I’m planning to play it.

I really don’t want anyone to feel obligated to help me, and I don’t want that pressure either. In graduate school I suffered through a couple of contrived mentoring arrangements, and it felt like a strange cocktail of awkward situations. The mentor and I met and fulfilled our obligations, but the relationship didn’t arise naturally. Here’s a breakdown of the feelings:

So, I’m not sure there’s any way to make this work if there’s not an organic evolution. It’s so easy for these kinds of things to turn phony.

As a writer with a couple of books under my belt and a couple more projects in the pipeline, I feel that it’s important to recognize the mentoring I’ve received. Writers who have spared some of their time to help me understand what the next leg of my own writing journey might look like. These people are the only ones who know what it’s like to wait on a contract that seems like it’s never going to come. They the ones who can tell you all the reasons to never respond to negative reviews on Good Reads. They can help you keep your cool when you’re out on submission. They can explain what pass through income is. All of this knowledge will come through channels, and later when you know these things, you take your turn.

In the end the best thing you can do as a mentor is share your enthusiasm and support. In many ways, this is the most important thing. Remind people that behind all the authors, there’s still a writer. The theorists were wrong. There was no “death of the author.” You can keep a journal of your own process, and you can be ready, like my most recent mentor, to send a simple message at the right time.

Keep typing. We’re writers, that’s what we do.

_____________________________

Todd Robert Petersen is represented by Nat Sobel of Sobel/Weber Associates. Originally a YMCA camp counselor from Portland, Oregon, Todd now directs Southern Utah University’s project-based learning program. You can find him online at toddrobertpetersen.com and @toddpetersen for tweets and Instagrams.